Providing our community with resources

- Food Literature Lending Library

- Compost Cats Program

- Spice Pantry

- Food Justice Book Club (past readings)

Food Literature Lending Library

The Tucson CSA Food Literature Lending Library was created to provide Tucson CSA members with another resource for learning about food. Currently, you’ll find everything from Thai vegetarian cookbooks to literature about agriculture’s role in the Black liberation movement. Although it’s small, we plan to continue to grow the library to include an array of authors, cuisines, and cultures. After all, diversity is what makes food so incredible! We’re using an online library catalogue called TinyCat that was specifically designed for tiny libraries like ours. You can check out our current catalogue by visiting www.librarycat.org/lib/TucsonCSA. We’ll need to set up an account for you before you can check out a book out from the Food Literature Lending Library. If you’re interested, please send us an email at tucsoncsa@tucsoncsa.org with the subject line “Lending Library Account” and include your full name, preferred email address, phone number, and address in the body of the email. Once we have this information, we can set up your TinyCat account and help you create a password. We would love to accept book donations to the library. If you have books related to cooking, food, and food systems that you would like to donate, please send us an email so that we can arrange a donation. Happy reading!

Start Reading!

To be added to our free library system, please send us a message so that we can create an account for you.

Contact UsCompost Cats at Tucson CSA

The University of Arizona Compost Cats Bucket Program is a residentially focused food scrap and compost collection. Compost is collected at pick up sites by Student Compost Specialists, (Tucson CSA is a new pick up site as of January 2022) and taken to the University of Arizona community garden to be composted and then sown back into the community garden. Compost Cats are part of the Office of Sustainability at the University of Arizona. Since the Bucket Program was launched in the Fall 2020, over 15,000 pounds of food scraps have been diverted from landfills!

Why Compost?

Composting is the natural process of transforming food scraps and other organic materials into a nutrient rich soil that promotes plant growth. Compost is beneficial to gardens and plants. From enhancing the plant health and plant resistance to common diseases; aiding healthy soil and symbiotic fungi that benefit plant roots; as well as helping plants retain moisture. Composting can help avoid harmful new greenhouse gases, such as methane, which stem from the decomposition of organic waste in landfills. Additionally, landfills have a lifespan and many are quickly approaching capacity and composting can help reduce the need for new landfills. Through the Compost Cats program, students can also be involved with the growing and redistribution of still-edible foods through programs like the Community Food Bank.

How the Bucket Program works

First things first, fill out an interest form when the Compost Cats are set up during share pick up. On this form you will pick whether you would like a 2-gallon or 5-gallon bucket (supplied to you by the compost Cats) or if you would like to use your own container. At that time, there will be printed information available with the list of acceptable compostable items and those that are prohibited. During January, specialists will be on site to answer any questions and concerns you might have. Once you have your bucket you will simply fill your compost bucket and then bring it back the following week during share pick up for the Student Compost Specialists to turn into compost. Easy peasy!

There is a small monthly fee that goes along with the program for non-students. Students do get to participate in the program free. However, there is a One-Time Onboarding Fee that is for everyone, including students:

- 2-Gallon Bucket: $20

- 5-Gallon Bucket: $30

- Own Container: $20

Once the One-Time Onboarding Fee is made, then the monthly fee for non-students is $12. Non-Students that enroll for a full year are eligible for one month free when the entire amount ($132) is paid upfront.

Ask any questions you may have and find out more info during your CSA pick up!

The Spice Pantry

Tucson CSA advisory board member Zeba Basu and her daughter Ela have been making wonderful cooking videos that demonstrate how to make authentic dishes from Zeba’s home country of India. To go hand in-hand with the cooking videos (which you can find on our YouTube channel), Zeba is stocking a spice pantry at Tucson CSA to make her recipes even more accessible. Have you ever wanted to try cooking an authentic Indian recipe but didn’t know where to find the spices? Or, perhaps you hesitated to buy a whole container of a spice you might never use again. The spice pantry will allow you to take home small amounts of the spices called for in Zeba’s recipes so that you can easily make them at home. The spices available include asaphatida, cumin powder, turmeric powder, panch poran, mustard seeds, cumin seeds, nigella seeds, and curry leaves. If you’re interested in taking some home, please see the CSA Shop volunteer inside of the courtyard so that they can retrieve them for you. There is no cost to take home spices, but feel free to leave a small donation to help Zeba replenish the stash in the future!

The Food Justice Book Club

The Food Justice Book Club was a diverse three-book series that helped us to better understand the roles that race, social revolution, food sovereignty, and food justice play in our food system. For each book we read, we held a virtual book club meeting led by CSA member, former librarian, and indexer Amron Gravett. Although the book club meetings have ended, we encourage you to use the resources that Amron created (below) to host your own Food Justice Book Club with friends, family, or yourself.

Introduction – Food Justice

We are here to understand the cultural in “agricultural.” To frame the present and futures of gardening and farming through a clearer view of the past social, economic, and racial histories of food systems. We are going to dip into some academic fields such as urban sociology, environmental studies, public health, civil rights, and critical race theory, in order to understand more about the intersectionality of food with racial and social justice. We’ll talk about collective memory, cooperatives, land politics, poverty, racial segregation, slavery, and urban redevelopment, among other things.

Because we have chosen academic-leaning books, it is important to recognize the hundreds of hours that go into researching, interviewing, and writing these books. If food justice is a new subject for us, we will only develop a nascent understanding of the particulars through our discussions. There is a great deal to comprehend, to contextualize, and to apply and our hope is that this primer will encourage you and guide you to read further, in order to think deeper about larger social systems like racial injustice and inequality, land displacement, and loss and how they have affected the food on your own table and the people’s history that journeyed with it. We hope to understand how BIPOC farmers and gardeners are excavating the historical relationships among farming, oppression, and resistance and to make critical connections between the brutal racial history of the United States and its contemporary social, economic, and health consequences. According to Kirsten Valentine Cadieux and Rachel Slocum in their essay What does it mean to do food justice?, the foundation of food justice lies in four pillars: trauma/inequity, exchange, land, labor.

However, we will also discuss food’s connection to memory, or rather “edible memory” as Jennifer Jordan calls it. We hope to learn about social and cultural identities based on food and farming. Understanding the importance of these helps us support the need for continued agricultural biodiversity, edible landscapes, and just local and global food systems. In short, we’ll talk about food, place, and culture.

All of the following concepts are critical to understanding food justice but we won’t touch on them in this series in any specific way so I wanted to define them outright before we begin.

Big Ag – Refers to the industrialized food system based on capitalistic principles that prioritize profits and scale over the impacts on people and the environment.

BIPOC – This acronym stands for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. It is used to refer to African American, Asian, Caribbean, Indigenous, and Latinx communities and individuals, when more specific information on a person or group’s racial and/or ethnic identity is not known. It acknowledges and respects the complexity of racial and ethnic identities, which cannot be ascertained from observation. An example would be a public health professional who moved to the United States from Jamaica who is often misperceived as being African American but who self-identifies as Black and from the Global South.

Environmental Justice – A term used to refer to the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

Environmental Justice Movement – Was started by individuals, primarily people of color, who sought to address the inequity of environmental protection in their communities. Food Justice – refers to “the right to grow, sell, and eat [food that is] nutritious, affordable, culturally appropriate, and grown locally with care for the well-being of the land, workers, and animals” (Alkon and Agyeman 2011, 5)

Food Justice Movement – Is a grassroots initiative emerging from communities in response to food insecurity and economic pressures that prevent access to healthy, nutritious, and culturally appropriate foods.

Food Sovereignty – Means a community’s right to define their own food and agriculture systems. (Alkon and Agyeman 2011, 8)

Food insecurity —Llacking access to a sufficient quantity of affordable, nutritious food. For example, the Arizona Department of Economic Security, Hunger Advisory Council’s 2017 Action Plan states that 1 in 6 Arizonans is affected by food insecurity and an alarming 500,000 Arizonans will face a diet-related illness by 2030.

Food Desert – “Area[s] with limited access to affordable and nutritious foods, particularly such an area composed of predominantly lower income neighborhoods and communities.” Also known as “food apartheid” which is a more comprehensive term that looks at the whole food system, along with race, geography, faith, and economics.”

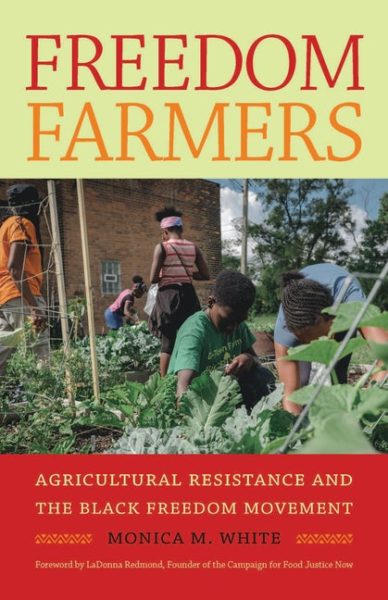

Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement

by Monica M. White

Author Biography

Dr. Monica M. White teaches courses in environmental justice, urban agriculture and community food systems at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is the first African American woman to earn tenure in both the College of Agricultural Life Sciences and the Gaylord Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. Her research investigates Black, Latinx and Indigenous grassroots organizations engaged in the development of sustainable, community food systems as a strategy to respond to issues of hunger and food inaccessibility. She has presented widely on these subjects, from University of Western Cape in South Africa to UC Berkeley to the Detroit Public Library. She is actively involved in speaking engagements all over the U.S. If you wish to watch a few of her presentations, or read some of her essays, she has quite a bit of content on her website at monicamariewhite.com.

White, Monica M. Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement. University of North Carolina Press, 2018

Discussion Questions

1. (chap 1, p38-45) Let’s begin with one of the Three Wise Men, as White called them. One of the ways that George Washington Carver was so effective in his work at the Tuskegee Institute during the turn of the century was his outreach educational projects. White notes that although he was an agricultural scientist, steeped in academic discourse and research, he connected with Tuskegee’s mission of understanding and respecting the limitations of the sharecropping and tenant farming systems. As such, he sought to address their immediate questions and spoke to the “simple farmer in plain language.” In what ways was this application of practical science useful and what lessons can we take from his success over 100 years later? Acknowledging his background (born as an enslaved person, kidnapped and then raised by a plantation owner, personal health issues, becoming an agricultural expert, and as the “only black man in the country who had graduate training in scientific agriculture”), how did this positionality reflect or engage with his work? What privileges and obstacles did it provide?

2.(chap 1, p51-56) Let’s continue with the last of the Three Wise Men, W.E.B. DuBois. How did he view Black cooperatives and what did he feel they provided for Black communities? How he view the idea of working for the common good as a way for Black people to reach personal and economic independence? How has he contributed to our modern understandings of social justice?

3. (chap 2, p70-74) White calls Fannie Lou Hamer an organic intellectual. What does that mean and how is this different from Washington, Carver, and DuBois? How does this play out in her activism? In what ways can we connect her work with the Freedom Farm Cooperative (FFC) with DuBois’ social theories? How did they both connect land & citizenship rights, and in particular, how did FFC do so through the various projects (voting, housing, education, economic projects, sewing co-op, tool bank)?

4. (chap 3) Where FFC’s mission centered it’s self-sufficiency model in politics and racial inequalities, North Bolivar County Farm Cooperative (NBCFC) centered it’s self-sufficiency model in poverty and hunger reduction. In what ways did these differing strategies lead to each of their successes or failures? In what ways was/is racial disadvantage codified (both formally and informally) in Mississippi? How does this affect the work of these collectives (FFC, NBCFC)? Are there any parallels in Arizona law?

5. (chap 4, p110-112) The Federation of Southern Cooperatives (FSC) was a direct result of the cooperative movement, as well as the civil rights movement of the 1960s. In what ways, was the FSC unique? (Zero interest business loans, co-op fishing production, shared crop rotation, health and education programs.) How did the FSC connect their farming with self-determination and political participation? What kind of backlash did they receive? (Eviction, job loss, intimidation, audits, denied federal funding.)

6. (chap 5) Detroit Black Community Food Security Network (DBCFSN) is an explicitly antiracist, anticapitalist, self-determined, self-reliance initiative. How did it play a role in the establishment of the D-Town Farm? In what ways does it serve as a model in urban agricultural projects? How does White show that it provides more than food for Detroit’s Black community? (programming, political change, site of training for self-sufficiency and political agency) How is D-Town Farm similar to Hamer’s FFC?

7. (chap 5) How does White connect the history of the auto industry and music of Detroit, with the current urban agricultural movement? (innovation, labor, creativity) Why are these features important to highlight and how do they help us connect with our understanding of other urban food projects? For example, what are some threads in Tucson or Arizona history that might inform our urban agricultural work?

8. (chap 5 and 6) Speaking broadly and with the example of Detroit that White highlights, how has urban development affected local/regional food planning? Does that still affect today’s food growers, intermediaries, and home-based food businesses? How does the idea of a “modern city” assert control on urban gardening and farming?

9. What are some of the ways that farmers and gardeners in the book expressed that their work was about more than producing food? How did they connect food scarcity with lack of access to medical care and job opportunities, for example? How did they explicitly and implicitly connect food to well being?

10. Historical narratives have tended to focus more on Black struggle (protests, marches, Freedom Riders, etc.), rather than on a legacy of horticultural knowledge, collective successes and community building, successful challenges to white supremacy through food production and political self-determination. White has provided a history of Black farming and cooperatives in this book that perhaps transforms our understanding of the history of Black communities and their relationship to the land. Do you think that was her goal? Did she succeed?

About the Author

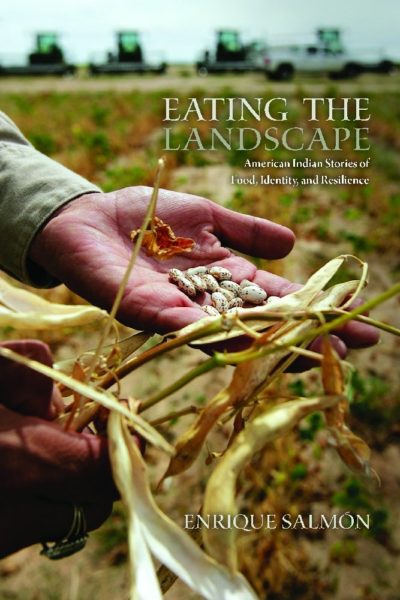

Dr. Enrique Salmón is a Rarámuri (Tarahumara). He feels indigenous cultural concepts of the natural world are only part of a complex and sophisticated understanding of landscapes and biocultural diversity, and he has dedicated his studies to Ethnobiology, Agroecology, and Ancestral Ecological Knowledge in order to better understand his own and other cultural perceptions of culture, landscapes, and place.

Dr. Salmón has a B.S. from Western New Mexico University, an MAT in Southwestern Studies from Colorado College, and holds a PhD in anthropology from Arizona State University. His dissertation was a study of how the bio-region of the Rarámuri people of the Sierra Madres of Chihuahua, Mexico influences their language and thought. Enrique has been a Scholar-in-Residence at the Heard Museum, and on the Board of Directors of the Society of Ethnobiology. He currently teaches American Indian Studies in the Department of Ethnic Studies at Cal State University East Bay.

Dr. Salmon’s recent studies have led him to seriously consider the connections between Climate Change and Indigenous traditional food ways. Indigenous homelands have been noticing the effects of Global Warming and Climate Changes first, but they are also able to possibly offer solutions for ways to feed the planet due to the resilience of traditional food ways worldwide. Food ways are connected to every element and process of sustainable bio-cultural diversity meaning that all facets of sustainable food ways including cultural expressions, landscapes, education, leadership development, networking, and policy and should be understood and supported.

Dr. Salmon has published several articles and chapters on Indigenous Ethnobotany, agriculture, nutrition, and traditional ecological knowledge. He has published two books: Eating The Landscape: American Indian Stories of Food, Identity, and Resilience (published in 2012). Eating The Landscape is Salmon’s book focused on small-scale Native farmers of the Greater Southwest and their role in maintaining biocultural diversity and which we will discuss in a moment. His second book out in September 2020 is titled Iwígara, the Kinship of Plants and People: American Indian Ethnobotanical Traditions and Science (pub’d by Timber Press). In this new book he provides a beautifully illustrated and philosophically uplifting guide to indigenous North American plant use. In it he delves into the spiritual beliefs of various cultures, including the Pueblo peoples of New Mexico and Arizona; the Cherokee, who once inhabited southeastern marshes; and his own people, the Rarámuri of Chihuahua, Mexico, originators of the “iwígara” concept “that all life, spiritual and physical, is interconnected in a continual cycle.”

Discussion Questions

(Hint: Don’t forget to refer to the index in the back of the book if you need a hint as to where the concept was discussed in the book.)

- What does the author mean by the phrase eating the landscape? How does culture shape the edible landscape? How is eating a cultural act? Do you think food can give us a sense of cultural belonging? How are seeds a cultural artifact?

- Several times in the book, Salmón references that there is a strong connection between cultural diversity and biodiversity. How does this biocultural diversity increase our means of survival? How does he use his homeland of the Sierra Tarahumara as an example of this? How do people enhance the diversity of their landscape through food production? What other regional examples of this does he give in the book?

- How does Salmón suggest that we regenerate our edible landscapes? What cultural practices are being utilized to do this? What examples does he give of successful cultural survival through modern agricultural projects?

- What is the Rarámuri concept of iwígara and how does it enhance our understanding of a plant-people interconnectivity in opposition to a “hierarchy of privilege” in the natural world?

- What are some of the circumstances and conflicts that threaten the small-scale New Mexico chili production today? Are those same issues affecting our staple crops here in Arizona? Which ones and how are they being threatened?

- The Georgia peach and the American Halloween pumpkin are examples of agrarian myth-making. In what ways does Salmón express his own form of myth-making, even his use of nostalgia, in this book? Why is this an important feature of modern food security and cultural identity? Is it effective? Why or why not?

- “Piki acts as mental refugia of cultural memory, cultural survival, and identity. Piki can even activate ecological knowledge related to agricultural techniques and wild crafting culinary ash. It is a spring of resilience that gushes forth when it is eaten.” (page 141) How does Salmón explain that the chili peppers, piki bread, and posole are forms of cultural resiliency? How does he connect this act of growing and making these unique foods to sovereignty, identity-based lifeways, and community responsibility?

- What new information did you learn about the Sonoran desert edible and cultural landscapes?

Additional organizations and links that Salmón references in our book:

NĀTIFS (North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems) Indigenous Food Lab:https://www.natifs.org/indigenous-food-lab/

RAFT (Renewing America’s Food Traditions): https://www.albc-usa.org/RAFT/ourwork.html

Cultural Conservancy (a Native-led nonprofit), Native Foodways program: https://www.nativeland.org/native-foodways

Native Seed Pod: an antidote to the monoculture (podcast by Cultural Conservancy): https://www.nativeseedpod.org/

Native Seeds/SEARCH (Tucson nonprofit seed conservation organization): https://www.nativeseeds.org/

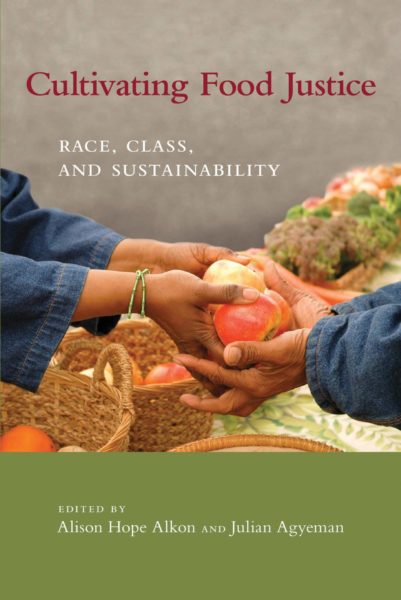

Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability by Alison Hope Alkon and Julian Agyeman

About the editors:

Alison Hope Alkon is Associate Professor of Sociology at University of the Pacific. Broadly, her research investigates the intersections between race, class, and sustainable food systems. Her work has explored the ways that racial identities are (pre)formed through engagement with sustainable food systems, and critiqued the limits of green capitalist strategies such as the buying and selling of local organic food in creating social justice and environmental sustainability. Alison is the author of Black, White, and Green: Farmers Markets, Race, and the Green Economy (2012), and co-editor (with Julian Agyeman) of Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class and Sustainability (2011). She has a great TED talk from 2018 titled “Food as Radical Empathy” available on YouTube here: https://youtu.be/f3aW-5qmblY

Julian Agyeman is a Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts, USA. He is the originator of the concept of ‘just sustainabilities,’ which explores the intersecting goals of social justice and environmental sustainability, defined as ‘the need to ensure a better quality of life for all, now and into the future, in a just and equitable manner, whilst living within the limits of supporting ecosystems.’ He has written 12 books. You can read more about his work at https://julianagyeman.com/books/

Book Introduction

This book is a great foundation in understanding the multiple theories, strategies, and language of food justice. We learned about so many of our big keyword terms in this academic-leaning book. One aspect of this book that I really appreciated was the addition of activist voices. This book is a part of the MIT Press series on Food, Health, and the Environment which includes 18 other books of note. They cover hunger, meat, organic farming, immigration, immigrant foods, GMOs, pesticides, and also focus on a few specific regions. I encourage you to investigate this series: https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/series/food-health-and-environment

Discussion Questions

- In chapter 4, how do the authors connect the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), Japanese Alien Laws (1913-1927), and the Internment Act (1942) with the issues facing Chinese, Japanese, and Hmong farmers and farmworkers today? How did they define the racial makeup of land ownership at that time, and are their lingering effects (land dispossession and racial othering) stemming from those legal parameters today? What unique challenges do Hmong farmers (from Laos and Cambodia) face today? (family labor, uninsured)

- In chapter 10, the author addresses “color blindness” (refusing to see race, or the absence of racial identifiers) and whiteness (which they define on p223) and discusses how they play out in vegan culture. How does our language in these spaces, such as the use of terms like “exotic,” affect the conversation of belonging, othering, and centering whiteness in alternative food movements? How can these cultural spaces be more inclusive, inviting, and representative of those who believe in the values of veganism?

- In chapter 12, the authors centers the lens on farmers markets and CSAs as coded white spaces. What are examples that they give to support this idea? What are some criticisms of these alternative food institutions? And what are some suggestions for addressing this divide?

- In what ways do the issues written about in this book, only ten years old, feel out of date and lacking current resonance? What issues would you have wanted to see discussed?

- What are some of the practical food justice issues that our area is facing right now? How can we apply some of the knowledge that we’ve gained from these 3 books to the conversation?

- How can a personal commitment to food justice inform our daily practices and rituals?

Additional Resources for Further Exploration:

- Good Food Film Program Series on Arizona Food and Farming https://www.goodfoodfinderaz.com/good-food-film-program

- UA Center for Regional Food Studies https://foodstudies.arizona.edu/

- Civil Eats has a rich collection of current articles on food communities and the federal policies that affect them. https://civileats.com/category/food-and-policy/

- Pima County Public Library’s ‘Seeds for Thought’ Book Club (monthly, online discussions). This book club explores nonfiction titles on food systems and food culture, food and social justice, and sustainability. Organized by the folks who coordinate the PCPL Seed Library. https://pima.bibliocommons.com/events/5fa5b9ad17e1da2400c8cafa?_ga=2.41025314.1471954365.1620770313-1099509248.1619110005